The Communist Party of China’s (CPC) 19th Party Congress ended last Tuesday, presenting China with new political leadership, and a new political theory known as the ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’.

Although not much was said specifically about the space industry during the Congress, it seems space will remain an important part of President Xi’s plan to make China an ‘earthly paradise’ by 2050. A few brief mentions were made about it during a press conference held on October 18. For example, astronaut Jing Haipeng described China’s planned space station ‘a glorious mission’, according to the People’s Daily. The same party-owned website quoted other delegates as declaring that China will conduct an average of 30 launches per year by 2020, and overtake the US in some ‘key aerospace projects’ by 2045.

Now that the Congress is over, we’re recapping some of China’s major space goals as outlined in China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020), which was elaborated on in the White Paper on China’s Space Activities in 2016.

Launch Vehicles

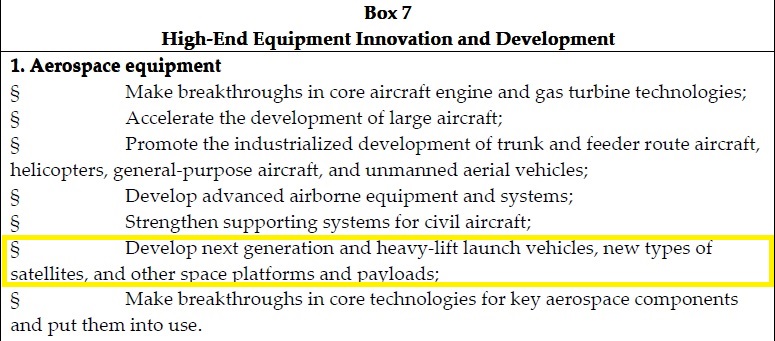

In the Five-Year Plan, the aerospace industry is labelled a ‘strategic emerging industry’, along with oceanography, information networks, life sciences and nuclear technology.

The White Paper elaborates on this, saying China’s space programme will first work on “high-thrust liquid oxygen and kerosene engines, and oxygen and hydrogen engines,” for heavy-lift launch vehicles. Although no exact vehicle is named, it is presumed that China’s next-generation heavy-lift rocket will be the Long March 9, currently under development and planned for launch in 2025. The rocket will be able to take 140,000kg to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and 50,000kg to Lunar Transfer Orbit (LTO).

Additionally, the White Paper also states that China is developing non-toxic and pollution-free medium-lift launch vehicles, probably to coincide with the CPC’s general aim of reducing pollution. There is also a mention of developing small, reusable launch vehicles; although China’s space programme has so far not announced developments in reusability, a China-based NewSpace company, Link Space, has been making progress in this area.

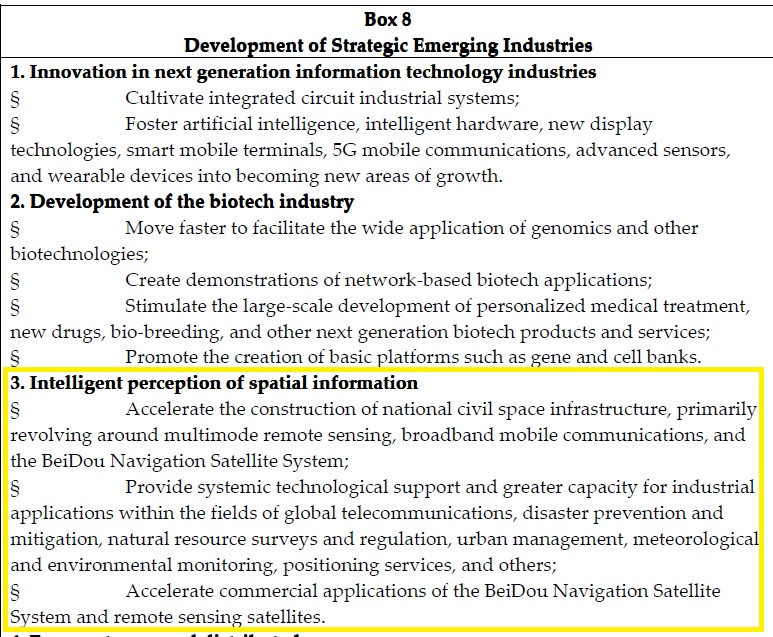

Satellites for Remote Sensing, Communications, and Navigation

Another aspect of the space industry highlighted in the Five-Year Plan is the use of satellites for remote sensing/Earth Observation, communications and navigation, along with the ground-based infrastructure needed to support large constellations.

The White Paper bolsters this by adding that China plans develop BeiDou “to start providing basic services to countries along the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-century Maritime Silk Road in 2018, form a network consisting of 35 satellites for global services by 2020”. In 2016, three BeiDou satellites were launched. So far this year, none have been launched, although China recently announced the launch of another three BeiDou satellites in November 2017.

Manned Missions, Deep Space Exploration & Quantum Experiments

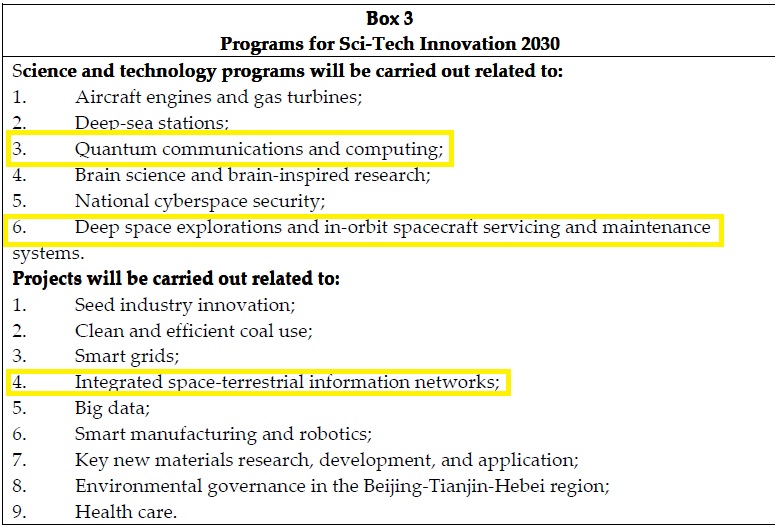

So far, China’s manned spaceflight, exploration missions and quantum experiments have attracted much global attention; these are also highlighted in the Five-Year Plan, as part of the country’s drive towards greater technological innovation and discoveries in frontier science.

So far, 2017 has seen China make great progress in these areas – the country’s Micius satellite, launched in 2016, has successfully conducted quantum entanglement and established a 2000km quantum communication link between Beijing and Austria. Also this year, China’s first cargo spacecraft Tianzhou-1 completed automated docking and refueling with its Tiangong-2 space lab, showing the country’s progress in running its own space station.

The White Paper mentions these activities, as well as describes China’s deep space exploration missions in greater detail. Two missions, in particular, are highlighted – (a) its moon mission comprising the Chang’e 5 lunar probe (slated to launch early to mid-2018, pushed back from end 2017) and the Chang’e 4 probe (slated to launch late 2018), which will make mankind’s first soft landing on the far side of the moon, and (b) its first Mars mission, scheduled for 2020, comprising an orbiter, lander and rover.

Frontier fields and space experiments

Although the Five-Year Plan does not specifically mention the types of frontier fields and experiments conducted in space, the White Paper describes several projects China has been publicizing lately. These include research into dark matter, which the White Paper specifies as being a “hard X-ray modulation telescope”. The telescope, known as HXMT, was launched on June 15, 2017.

Other specifics mentioned in the White Paper include the Shijian-10 recoverable satellite, which carried experiments in microgravity and space life science, and which returned to Earth in 2016. However, another experimental satellite, the Shijian-18, was lost in July this year due to a Long March-5 failure, causing a significant setback to China’s experimental satellite programme.

Conclusion

In 2018, China’s space highlights will probably be the Chang’e 5, postponed from this year, and possibly the Chang’e 4, originally scheduled for late 2018. Next year will also see the second launch of the failed Shijian-18, and CFOSAT, a remote sensing satellite developed jointly by France and China. The next great leap forward for China’s space program will probably occur in 2020, if it succeeds in accomplishing three major tasks – a mission to Mars, completion of a space station, and in-orbit testing of a space-based solar power system that can beam energy back to Earth.

References:

1. The 13th Five-Year Plan (http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/20161/P020161207645765233498.pdf)

2. China’s Space Activities in 2016 (http://www.scio.gov.cn/zxbd/wz/Document/1537091/1537091.htm)