Last month, the European Commission organized a workshop to present Copernicus, the European Union Earth Observation programme, in Singapore. In conjunction with the event, SpaceTech Asia spoke to Dr Philippe Brunet, Director for Space Policy, Copernicus and Defence at the European Commission, to find out more about the Copernicus programme and its plans in Southeast Asia.

What is Copernicus? How do the Sentinel satellites fit into the Copernicus programme?

Generally, Copernicus is about global monitoring. So we designed the programme to acquire data from all over the world. It’s about the monitoring of the environment – monitoring of land, oceans, the atmosphere, and also of natural disasters, in emergencies. Plus we have a dedicated service dealing with climate change.

Copernicus is the programme. Sentinel are the dedicated satellites for Copernicus. One pillar of Copernicus is the Sentinel satellites. Another pillar is the in-situ data. We have a lot of buoys at sea. We have also in-situ sensors on the ground. And the third pillar is what we call the contributing missions from the EU member states. The Copernicus programme is the owner of the Sentinel data and of the Sentinel satellites.

Copernicus currently has six services. Five are publicly available and one is restricted – that’s about security, mainly border surveillance of Europe. The others are land monitoring, ocean monitoring, atmosphere monitoring, climate change and emergency situations, and are fully open to everybody.

Why did you decide to hold a workshop in Singapore? What are some of your activities and plans for the APAC region?

We’ve already had partnerships with North America and Latin America. We have a partnership now with Australia. The ASEAN countries and Asia in general are very important in order to assess certain global phenomenon.

For instance, for climate change, in order to assess the rise of the ocean – what we call altimetry – there are a lot of sensors about the atmospheric fluxes, for which it’s very important to have partnerships because we take the view that there is no competition between Earth Observation systems. The more you can exchange data with other systems, the more accurate are, finally, your findings.

What we want to create is a network to allow our partners to use the totality of the Sentinel data. Right now, people are using 2-3% of the Sentinel data. The partnership is about putting a kind of grid around the world, mainly using submarine cables.

The EU Commission has just adopted a new partnership with Asia, which partly deals with digital connectivity. We will be one of the main customers.

With this, you have the possibility to access the totality of the data. Right now, it’s possible, but to download just one radar image of, let’s say Typhoon Mangkhut, through normal technology, you have to spend one week.

Do take a moment to subscribe to our email newsletter here. We will not sell your email address to a third party, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

So we are creating hub-to-hub technology. The first agreement we had was with the USA, and that was the first time we experimented with it. But we need an agreement to do that, because, if another hub is created on the other side of the earth, we have to put in place certain things in Europe in order to feed this hub.

In this region, we have started to talk with the ASEAN Secretariat. Currently, we have 2 or 3 countries who want to develop bilaterally. That does not mean that it will not benefit the other ASEAN countries. Because for instance, if we have hubs in Jakarta and Singapore, it will be very easy for Malaysia or the Philippines to have sub-regional hubs. Because it is easier to create a mirror hub in Manila from Jakarta than from Berlin or Paris.

How does the Copernicus programme store such a large amount of data?

We are now generating nearly 1 petabyte of data every 3 months. Since the launch of Copernicus, we have in the archives something like 11 to 12 petabytes of data.

Some of the archives need to be consulted every hour, and some by the month, and some historically. So now we’ll introduce this tiering of archives first. We had a budget, when Copernicus was launched in 2014, for different centres to process and archive both the raw data and the product. This plan should have run smoothly till 2021, but I think that we will be completely full by the end of the year. This means that we are renting additional facilities. Because not only do we have to archive all this data, but by law, we have the obligation to have backup. Plus, we have to organize the data by satellites (there are six categories), and by services.

To address this, we have three measures. The first is to redesign the archives, and the second, to extend our capacity.

The third is a new approach we have developed to boost the ecosystem, in particular vis-à-vis the downstream industries. Because a lot of people making applications, in particular for the smartphone, are SMEs with no cash flow for large IT infrastructure. So have launched a new initiative in order to trigger the formation of consortia in Europe, putting together companies dealing with space application, telecom, with cloud and computing technologies, and with archives. We have 5 consortia, and these consortia have to maintain all of the Copernicus data products for free, openly accessible to everybody. But of course, they do some business because they can rent some part of their cloud, they can rent some of their algorithms.

How can SMEs in Asia use Copernicus?

The aim is to have the end user build applications on top of that data. And one of the main lessons from the last couple of years is that, from a system which was designed at the very beginning to serve public objectives, it has become an economic tool boosting the downstream sector. From data processing to algorithms – activities around big data are mushrooming.

If you master the algorithm or you have new ideas, you have the raw materials to run your business.

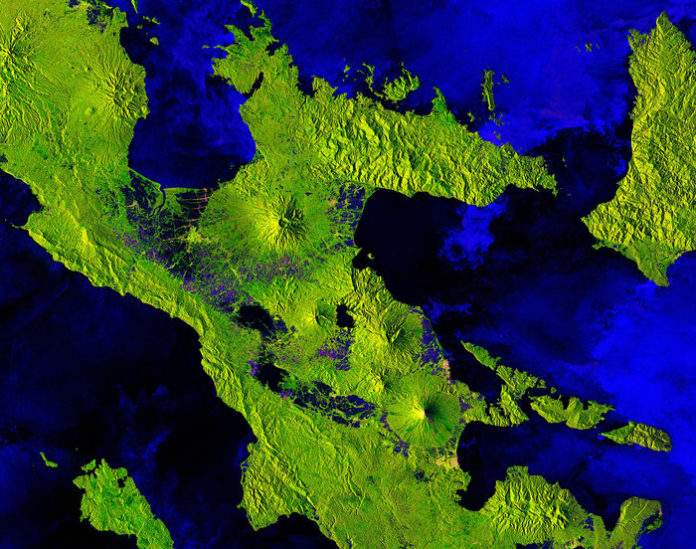

For instance, you can use data from Sentinel-2, which is a pair of satellites that together orbit the Earth every 45 minutes. Of course, here you are close to the equator, so the Sentinel will not pass by every 45 min, but the longest period I think is 2.5 days. For most of the applications, 2.5 days is a huge qualitative and quantitative jump, because with the other technologies, it’s 2 weeks. So if you want, in Singapore or Malaysia or Indonesia, you can develop applications for deforestation, where having the same picture every 2 days is largely sufficient. With this, you can even track where the illegal logging has been taking place.

You have in Europe applications which tell you when you should water your golf course, taking into account the geology, etc. If there are people in Singapore who want to adapt European products or to process raw data to create brand new products for Singapore, they could do that. Of course, it’s nothing compared to challenges like climate change or Carbon Dioxide monitoring, but it creates a lot of added value, it creates a lot of wealth, and a lot of jobs.